Lady Muleskinner Press: Writings of Burgin Mathews

Lady Muleskinner was an independent, living-room press and the publisher of Singing Governors, Fiddling Senators, and Other Country-Music Politicians, as well as of other eventual short works. (Note: See “Cheap Buys” for subsequent publications.)

Ladymuleskinnerpress.com was the internet home of writings by Burgin Mathews.

Selected content is from the site's archived pages providing just a small sample of what Burgin Mathews offered his readership.

Do enjoy.

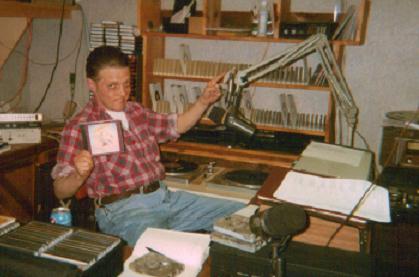

Interested in Burgin Mathews? He is the host of THE LOST CHILD which brings one hour of jam-packed hour of down home American music: honky-tonk country, blues, gospel, old-time fiddle & banjo, Western swing, jazz, soul, Cajun gold, rock & roll, boogie-woogie, zydeco, bluegrass, high lonesome hokum and more. Available only at Birmingham Mountain Radio: listen online locally at 107.3, or stream it--wherever you are--at www.bhammountainradio.com. Each Saturday's show is rebroadcast Tuesday nights, 11 to midnight.

About

Burgin Mathews is a writer and teacher in Birmingham, Alabama.

Lady Muleskinner is an independent, living-room press and the publisher of Singing Governors, Fiddling Senators, and Other Country-Music Politicians, as well as of other eventual short works. (Note: See “Cheap Buys” for subsequent publications.)

Ladymuleskinnerpress.com is the internet home of writings by Burgin Mathews.

(About the name)

The name of the press and website comes from Dolly Parton’s “Muleskinner Blues.”

Some background:

There is no song more representative of country music’s tangled history—few songs, perhaps, more representative of the entire tangle of American music history—than “Muleskinner Blues (Blue Yodel No. 8).” It is the Leonard Zelig of country songs, cropping up over and over in different guises at various milestones of the music, beginning with the original 1930 recording by its composer, the esteemed “Father of Country Music,” “Blue Yodeler” and “Singing Brakeman” Jimmie Rodgers. A few years later it became a staple in the repertoire of the Monroe Brothers (Bill and Charlie) and, as brother Bill and his Bluegrass Boys begat a new sound of their own, “Muleskinner Blues” would be invented all over as one of the hallmarks of the new genre bluegrass.The Boys’ “Muleskinner Blues” announced the arrival of a whole new thing: listen to the 1939 version from The Music of Bill Monroe boxed set and to the 1973 version from Monroe’s Bean Blossom album for the ultimate expressions of the bluegrass drive. If the first performance unleashes a new kind of energy and sound from an old standard (“The number’s a hot one,” the Grand Ole Opry announcer predicts)—the first sounds of what would before long become a distinct musical genre—the later Bean Blossom recording represents Monroe reveling in the full-fledged force of the bluegrass thing.

(Fiddler Jim Shumate, one of the earliest Bluegrass Boys, quoted in the notes to the Monroe box: “‘Muleskinner Blues’ was hot as a pistol when I was with Bill Monroe.I’d say, ‘Bill you’re going to have to lay the mule on ‘em.’ He could always lift them with ‘Muleskinner.’”)

When, then, Dolly Parton picked up the thread in 1970 she was herself consciously partaking in history-making. The song already was rich with connotation (it had also, in the 50s and 60s, been reworked as an early rocker, each in turn by Lonnie Donegan, Joe D. Gibson, and the Fendermen). To re-imagine, again, “Muleskinner Blues,” was to build on Rodgers and Monroe and the others and to re-imagine, again, the very rules of country music.Dolly had debuted on the Grand Ole Opry in 1959, at thirteen; in 1960 she cut “Puppy Love,” her first single, for the Goldband record label and in 1967 she had her real breakthrough with “Dumb Blonde.”Porter Wagoner hired her onto his TV show and they recorded a string of successful duets, but she was unable really to sell herself as a solo act until “Muleskinner Blues.”Play the song and, even now, it announces, wildly, its own whole new thing, the opening hook and Dolly’s first whistle and whipcrack onward.

It is a great song, and it sings of revolution. Just as Aretha Franklin, a few years previous, had altered forever the meaning of Otis Redding’s “Respect” by recording, and crucially re-gendering, it (“All I’m asking is for a little respect when you get home,” as danceable as it was sung by Otis, was suddenly not only more danceable than before but also, sung by Aretha, loaded with social and political meaning that transcended the tradition of the “cover” song)—so does Dolly’s Blue Yodel transform the meaning of the old song and transform, at that, the very possibilities of the man’s-world of country music. As with Aretha’s “Respect,” this was more than mere cover-ing. When, in the second verse, Dolly adjusts the familiar lyrics to announce “I’m a lady muleskinner, from down old Tennessee-way, hey hey,” it is clear that there is no going back.

* *

As significant a moment as this may be, and as significant as the song’s overall career may be, I should admit that there may be no overarching message in the selection of that line as the name of this new press. Or the overarching message, if it exists, could be incidental or even a happy accident, I’m not sure. I do know that since I first heard Dolly Parton’s “Muleskinner Blues” some years ago that phrase has captivated my imagination. I have imagined it on homemade t-shirts (black puffy letters ironed onto a dark blue or deep yellow) and have thought it a good idea for a band name; I can imagine also a drag queen adopting the title. When I needed a name for my press, at any rate, this was the first phrase to come into my head and it would not leave.

Lady Muleskinner Press’ first offering, after all, plumbs the history of country music, offering a guide to fiddlers, crooners, guitar- and banjo-pickers who have doubled as politicians; other writings on this website also tend to lean heavily on themes of downhome music. Or the theme, more broadly, of Southern culture—see the essay on W.C. Rice, or the links to Speak Magazine and Railroad Bill, the Alabama outlaw. But ultimately the website will grow more general than that, too, encompassing whatever my writing or my living-room press decides to take on. An upcoming essay will celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of The Muppet Movie, and there is a small book of poetry afoot and, later, more. Other interests will very gradually follow. For all of that, though, I expect that this will remain primarily a downhome operation, heavy especially on the music. And though I can not claim the operation itself revolutionary maybe some of that spirit will rub off, too, and maybe some of the high-geared hell-for-leather energy that is part of the “Muleskinner Blues” legacy, lady-muleskinner and otherwise.

Finally, and while I am at it: if you have not ever done so, or not done so lately, tonight you should listen back-to-back to every version of “Muleskinner Blues (Blue Yodel No. 8)” you can obtain, downloaded or however; certainly to the versions listed above.But there are also these good ones, and more, too: Woody Guthrie’s; the Maddox Brothers & Rose’s; Ramblin’ Jack Elliot’s, from the opening scene of the movie The Ballad of Ramblin’ Jack, recorded originally for The Johnny Cash Show; Odetta’s; the Cramps’. Kilby Snow has a great instrumental take on the autoharp. Listen to them, ideally, in chronological order. Harder to find (available as far as I know only on LP) is the Parton-influenced take by Otis Williams (African American r&b-turned-country singer) and the Midnight Cowboys. And there are other, if less crucial, manifestations. The Meat Purveyors did it as “Lady Muleskinner,” and a number of bluegraass acts have recorded it in pretty straight covers of either the Monroe or the Parton molds. Also related, vaguely (compare it to the Fendermen record for the clearest connection), is this 1970s Levi’s commercial.

Laughing Levis Commercial

Enough about the name and enough about what this all is. Thanks for visiting Lady Muleskinner Press. Check back when you can for updates and additions.

Take care.

– November, 2008

NOTE: Jocelyn Neal exhaustively and insightfully explores the rich and winding career of “Muleskinner Blues” in her book, The Songs of Jimmy Rodgers (Chapter Two: “Why Everybody Wanted to Be a Muleskinner.”) My own thinking about the song was doubtlessly influenced by conversations in Neal’s graduate course on country music at the University of North Carolina, circa 2004. The book, a recommended read, examines the lasting impact a handful of Rodgers’ songs have made on our culture — and the interesting impacts, also, our shifting culture has made on those songs.

POSTS FROM 2012 -

The Magic Sun: An Interview with Filmmaker Phill Niblock

FRIDAY, MAY 25, 2012, the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame and Birmingham Mountain Radio’s The Lost Child will present A SUN RA CELEBRATION: an evening of music, film, reminiscence, and poetry in honor of jazz legend and spaceways traveler, Herman “Sonny” Blount, aka Sun Ra. (For more on Sun Ra and on this event.) The evening—which will also feature live music, poetry performance, and a short talk by “Doc” Adams, one of Sun Ra’s earliest bandmates—will conclude with a screening of Phill Niblock’s short (sixteen-minute) film, The Magic Sun. Filmed between 1966 to 1968, The Magic Sun captures three performances by Sun Ra and his Solar Arkestra: “Celestial Fantasy,” “Shadow World,” and “Strange Strings.” Rather than simply film the musicians at work, Niblock creates a sort of visual equivalent to the band’s abstract, other-worldly expressions. His film is a unique and hypnotizing experience in sound and image, full of extreme close-ups, shifting black-and-white imagery, abstract movement, and its own kind of visual rhythm.

Niblock is himself a prolific and influential experimental composer based in New York City. In the interview below, he describes the process of creating this early film, placing it in the context of his evolving career.

How did the Sun Ra project come about?

A mutual friend [Martin Bough] who is a photographer and also a jazz musician, and we worked together extensively a year or so before, shooting sessions for United Artists—photographing. He knew Sun Ra, and Sonny was talking to him about a film; so he asked me if I would be interested, because I had since then began to shoot film. So, in ’66 I had this idea of something I could shoot in twenty minutes and that would be the film; that would be enough. Two years later, I was still struggling to find the right stuff—but I did. We shot many times, and there was an extensive amount of research: in working with film stocks, print stocks, and lab tests.

Tell me more about that research—you mean, in terms of the technical production of the film?

Well, I decided to do the high-contrast stuff, and the idea is that you don’t see anything in the black; you should not see the frame, either, of the film. So part of it was picking stocks, and I eventually evolved to shooting on a high-contrast, black-and-white stock normally made and used just to shoot titles. It’s a very slow speed, so that required a lot of light to get a good exposure. I solved that partly because I was shooting directly into a light bulb: so in the second two-thirds of the film, the light you see in the frame, the sort of sun shape, is actually a 60-watt light bulb—or more, I’m not sure how big the wattage was—and I’m just silhouetting fingers and stuff like that, against the light. The first part of the film actually was shot with the reversal stock. It appears to be negative, because it’s printed on a negative stock.

And up to then your work had primarily been as a still photographer? Where were you, professionally, at that point?

Well, I was doing jazz musicians myself as an amateur photographer in ’60, ’61, to ’64. Then there was a couple of years, for a year and a half, where I was photographing for United Artists, doing sessions, and Martin and I did that together. But I began to make films in ’65, and I was also printing a lot of stuff—I had a one-man show in the only photography gallery in New York at that time, in ’66, and after that I just stopped doing darkroom work; I stopped printing, and concentrated much more on making films. So ’66 was a very early time for film for me—I learned a lot in the next three years, while I was finishing the Sun Ra film.

What can you tell me about the experience of working with Sun Ra himself?

He was very nice to work with. The whole band was nice to work with. We shot the second two-thirds in the apartment they had, where they lived very communally on 2nd Ave. and 2nd St.—that’s what I remember the address was. The first part was shot on the roof of the same building, on a bright, sunny day: just went out on the roof one day in the summertime and shot the material. I don’t even know where I shot the other stuff—because it’s all in cans somewhere and I haven’t looked at it since ‘65 or ‘66, ‘67.

He was playing a lot at Slug’s, which was a club on the Lower Side on Third Street, Avenue C—which was a very hip place, but it was a very rough area because it was a very heavily drug-infested area in those days. And I would take a 16-mm projector down and project the film on the bandstand, as I was making different versions of the film; so it showed on a wall behind, but it also showed on the musicians themselves. I must have done it, like, a dozen times. And then in ‘69 Sun Ra had a concert at Carnegie Hall, and we showed the film on the back of the stage, something like thirty-five feet wide, with a xenon arc projector. By then it was finished, so the film is what you now see.

About the time you finished the Sun Ra project, you were transitioning, yourself, from film to music, which has been the focus of most of your career. Can you describe how you came into music, as a composer and performer?

I began to film with a filmmaker and choreographer, Elaine Summers, who eventually founded Experimental Intermedia, which is the organization I’m now director of, since ’85. She was very connected to the Judson Dance Theater, which was the real seat of post-Cunningham dance in New York—so an incredible amount of experimentation. I began to film dancers and do stuff for choreographers, myself, making intermedia performance with multiple image projections and sound and sections of live dance. I had some collaborations under my belt, and I didn’t like collaborating; I knew what I wanted for music, and I didn’t want to go about trying to get it from somewhere else and not be satisfied—so I just started making music. And the ideas that I had for making music are exactly what I have worked with since—they haven’t really changed.

How would you define those ideas?

Well, I’ve been working with tones that are very close together in pitch but produce other resultant tones; and especially working with instrumental sounds, not with electronic sounds, so that the rich timbre of the instrument itself creates an incredible range of overtone patterns, as the tones that are pushed together in pitch meet against each other.

Phew. How’s that?

Note: Since the birth of Experimental Intermedia in 1968, Niblock has hosted over a thousand performances in his legendary SoHo loft space. At seventy-nine, Niblock remains today a true creative force—as a composer, performer, curator, and kind of avant-garde guru.

This interview was conducted by phone in the spring of 2012. The advertisement for “A Sun Ra Celebration,” included on this page, features a black-and-white still from Niblock’s film. Photo of the Carver Theatre by Burgin Mathews.

“He Was What He Was”: Alabama Jazz Legend “Doc” Adams on the Life and Music of Sun Ra

— Sun Ra, The Birmingham News, 1988

FRIDAY, MAY 25, 2012, the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame and Birmingham Mountain Radio’s The Lost Child present A SUN RA CELEBRATION: an evening of music, film, reminiscence, and poetry in honor of jazz legend and spaceways traveler, Herman “Sonny” (Sun Ra) Blount.

Sun Ra was one of jazz music’s most creative, prolific, and outrageous personalities, a composer, bandleader, poet, and philosopher whose home, he said, was outer space and whose mission was to communicate cosmic truths—via his band, the Intergalactic Arkestra—to the lost citizens of this poor planet. Through the medium of music Sun Ra sought to expand the narrow consciousness of mankind, tuning us in to the interplanetary vibrations and opening us up to a greater harmony with ourselves, with each other, and with the larger universe.

Sun Ra was devoted entirely to his task, consuming himself, his whole life, with his music and outer-space philosophy. If, with his colorful gowns and ceaseless talk, he was an eccentric, his eccentricity was no put-on or cheap gimmick. As a musician his tastes were diverse, his ear acute, and his talents wide-ranging; he bended musical genres, taking in and riffing on the broad sweep of the jazz tradition, while pushing his musicians and his listeners into strange—and sometimes liberating—new places. His critiques and observations of the human race, if often couched in bizarre and convoluted discussions of space and mythology, contained moments of eye-opening and original insight. And he believed, wholeheartedly, in his mission.

Sun Ra returns to Birmingham for a legendary concert at the Nick, 1989 / photo courtesy Craig Legg

The upcoming Sun Ra Celebration will pay tribute to Sun Ra and his Birmingham roots in a variety of ways. First, Birmingham jazz legend Frank “Doc” Adams, who, in the 1940s, played in Sun Ra’s original band, will perform his own tribute to Sun Ra and discuss his experiences with his early bandleader. Birmingham spoken-word poet Voice Porter will present selections of Sun Ra’s original poetry. Prizes will be given out throughout the night, courtesy of The Lost Child and Sun Ra Research, a California-based operation which, for going on three decades, has been devotedly documenting the Sun Ra story. The Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame’s museum and bar will be open to visitors throughout the evening. Finally, Phill Niblock’s classic short film, 1968’s The Magic Sun, will be shown on the big screen of the Hall of Fame’s historic theatre. A program booklet will offer additional context on Sun Ra’s life and music.

Editor's note: In an effort to find a complete catalog of Sun Ra's works, we hired a data science developer to gather as much data from as many sources as possible. He then put us in touch with a consultant for DevOps who helped us create a special app to sort through the huge amount of literature on this artist. We had over 50 gigs of records, notes and articles, so a data savvy developer was really helpful. It's hard to believe that a single artist inspired so much content, but we're glad he did and our understanding of his life and work has benefitted greatly from this work.What follows, here, are two excerpts from a recent interview with Frank “Doc” Adams, in which he discusses the constellation of musicians that formed around Sun Ra in 1940s Birmingham. Adams, who played in Sun Ra’s band as a teenager, was also a member, at that time, of John T. “Fess” Whatley’s Vibraphone Cathedral Orchestra, Birmingham’s preeminent “society” dance band. In the years to follow Adams would play alongside Erskine Hawkins, Duke Ellington, and many others. Today, he is the Director of Education, Emeritus, for the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame. He is a lifelong educator, whose decades-long work with music in the Birmingham schools has left a tremendous impact on his community. His new book with Burgin Mathews, titled Doc: The Story of a Birmingham Jazz Man, is due out in October of 2012 from the University of Alabama Press and tells the story of Adams’ remarkable life in music. (Chapter Five, “Outer Space,” focuses specifically on Sun Ra and his Birmingham years.)

Frank "Doc" Adams, 2011 / photo by Garrison Lee

The following interview excerpts were recorded in Adams’ office at the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame. (Note: an interview with filmmaker, composer, and multimedia artist Phill Niblock, discussing the making of The Magic Sun, will appear soon on this website. The two advertisements featured on this page for A Sun Ra Celebration include black and white stills from Niblock’s film.)

Interview excerpt no. 1: “He was what he was.” Doc Adams on Sun Ra’s bandmates, part 1 (10:24)

Interview excerpt no. 2: “He was able to get out of people things that we weren’t able to get out of ourselves.” Doc Adams on Sun Ra, part 2 (7:11)

(Note: Big Joe Alexander, mentioned in the first interview clip, later played in the big bands of Woody Herman and Tadd Dameron. Also: in the second clip, Adams mentions local composer Dan Michael, who wrote some complex arrangements for Sonny Blount’s early band; he does not mention in this clip the fact that Michael was also a gifted one-armed pianist.)

For more info on A Sun Ra Celebration, join the Facebook invite page.

Do That Birmingham Stomp: Twenty Birmingham Songs

The city of Birmingham, Alabama, has inspired many musical tributes over the years, from the pens and instruments of natives and non-natives alike. For a few of these Birmingham songs, the place name may be more or less inconsequential, offering a convenient rhyme and rhythm and a generic southern locale; most Birmingham songs, though, are invested with a deeper sense of place and homegrown experience. While some extol wholeheartedly the draw and pleasure of the Birmingham life, others confront both the pain and the power of the city’s legacy. Taken together, these songs capture a broad sweep of our city’s story and sound.

The following essay appeared originally in the inaugural issue of Pavo, the late online magazine of arts and culture in Birmingham. Expanded to “Thirty Birmingham Songs,” a revised, enlarged and updated version was released in November 2011 as a pocket-sized guidebook from Lady Muleskinner Press. (See CHEAP BUYS for more info.)

The songs below are not arranged according to any strategy of ranking, and are not listed chronologically, but instead simply offer the ultimate Magic City playlist.

1. “Birmingham Boys,” Birmingham Jubilee Singers (1926). In the 1920s and ‘30s the Birmingham area boasted an African-American gospel quartet tradition whose impact stretched far: for years to come the harmony styles shaped in Jefferson County would prove a lasting well of influence for African-American vocal groups, both sacred and secular, across the country. Several local groups—The Famous Blue Jays, the Dunham Jubilee Singers, the Bessemer Sunset Four, the Kings of Harmony, and more—recorded commercially, and many toured the country professionally, spreading the gospel of the Birmingham Sound. By the 1940s traveling Birmingham groups had established bases in Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, Memphis, New Orleans, Cleveland, Dallas, and other cities, building wide followings and effectively changing the landscape of American gospel. One of the most successful of these outfits was the Birmingham Jubilee Singers, led by Charles Bridges, a quartet-trainer who had helped mold a number of groups in the local tradition. “Birmingham Boys,” the flipside of their first record, was the Singers’ calling card. A secular song in a mostly secular repertoire, “Birmingham Boys” is nonetheless typical of the area’s harmony-rich, a cappella quartet style, and it fittingly introduces new listeners to the home of the Jubilee movement. “Birmingham, Birmingham, Birmingham boys are we,” the lyrics proudly announce: “if you could live a Birmingham life, how happy you would be.”

2. “Fat Sam from Birmingham,” Louis Jordan (1947). One of many songs to make much of the easy rhyme of “Birmingham” with “Alabam,” “Fat Sam” is a swinging number about a larger-than-life character (“as wide as he is tall”) who hangs out in “front of Shorter’s bar” and, genial hook-up to whatever mischief you might need, serves as the ultimate good-times ambassador. It is pure and classic jumping ‘40s jive, shot through with Jordan’s characteristic relish. Not to be confused with Western-swinger Hank Penny’s “Big Footed Sam” from Birmingham (“his size fourteens really rock the floor…”), which is not so bad a tune itself.

3. “Birmingham Daddy,” Gene Autry (1931). A perfect little recording, among the very first sides cut by future cowboy-crooner Gene Autry. Before rising to Hollywood horse-opera stardom or entering his jingle-jangle jingles into the Christmas-pop canon, Autry recorded his share of earthier “hillbilly” blues. These first Autry recordings clearly evoked the style of the immensely popular Jimmie Rodgers, borrowing Rodgers’ yodel and some of his repertoire, but managed to showcase a voice that was nonetheless unique, and eminently listenable—edgier, too, than Autry’s soon-to-develop good-guy image would allow his future output. Among these early recordings is “Birmingham Daddy,” an Autry composition blessed by the jazz-infused banjo backing of string virtuoso Roy Smeck. The song deserves quoting: “If love was liquor, and I could drink, I’d be drunk all the time / I’d go back to town, in Birmingham, with the loving mama of mine.” Yodel-a-hee-hey.

4. “Birmingham Bounce,” Hardrock Gunter (1950). “In the heart of Dixie, in Alabam, there’s a place we love, called Birmingham.” So began Hardrock Gunter’s “Birmingham Bounce,” recorded in 1950 for the Bama record label—and so did Birmingham partake in the birth of rock and roll. The recording became a regional hit, Gunter’s first and biggest, and riding its success the Birmingham singer toured the Southeast, playing in empty airplane hangars, other venues apparently too cramped for his crowds. Gunter’s thing was part Western swing, part boogie-woogie—“a funny little rhythm with a solid sound,” the song said—and an immediate precursor to rock and roll. (Gunter himself was one of the first to use the phrase “rock and roll,” in 1950’s”Gonna Dance All Night,” recorded soon after the “Bounce.” It would still be another year before Jackie Brenston and Ike Turner cut “Rocket 88,” often lauded today as the “first” rock and roll record; four years still until Elvis; five until Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock.”) “Birmingham Bounce” spawned over 20 cover versions, extending the song’s reach far beyond Gunter’s tour circuit. Quick on the heels of the original, Red Foley took it to the number-one position on the country charts, and a striking variety of musicians released their own versions: country musicians Leon McAuliffe and Tex Williams; rhythm-and-blues pianist Amos Milburn; Big Band leaders Lionel Hampton and Tommy Dorsey. And so it was that in the days leading immediately into rock and roll, all over the country people were gearing up and getting primed—bouncing—Birmingham-style.

5. “Great Day for Me,” Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights Choir (circa 1963). In 1956, in the wake of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, state officials banned the NAACP from Alabama. Seeing the need for a new group that would challenge discrimination, the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth spearheaded the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Where the NAACP had used the courts to fight racist laws, the ACMHR called for more of a direct, confrontational, and community-rooted approach. In 1963, the group teamed with Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to launch “Project C” (for “Confrontation”), a period of direct and sustained demonstrations in the Birmingham streets. From April 3 to May 10, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church served as the home base for the demonstrations. Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor and Birmingham law enforcement responded violently, sparking outrage across the country.

As it did in all the movement’s battlegrounds, music provided significant fuel for the mass meetings and demonstrations in Birmingham. The ACMHR Choir, led by Carlton Reese, performed nightly at the Sixteenth Street church. One of their songs, “Great Day for Me,” adapted a gospel standard to the Birmingham moment:

Great day for me, great day for me

I’m so happy, I want to be free

Since Jesus came to Birmingham, I’m happy as can be

Oh, great day for me.

Neither Birmingham, nor the rest of the nation, would be the same again.

6. “Birmingham Mistake,” Sammi Smith (1973). Sammi Smith scored a major hit in 1971 with her version of Kris Kristofferson’s “Help Me Make it Through the Night,” a success which should have marked the start of a celebrated career; sadly, and despite some powerful performances to her credit, Smith never quite pulled off the larger success that her deep, sultry voice may have deserved. “Birmingham Mistake” is the story of a woman whose bad luck began with her own unwanted birth and her subsequent abandonment, in a basket, on a run-down Birmingham doorstep. The singer’s plight hinges on the chance turns of her fate, beginning with the sorry doorstep selected by the mother she never knew: “I wish now that I’d been put down,” Smith sings, “in a better part of this town, when she got rid of a Birmingham mistake.” Despite some uninspired lyrics (“Life ain’t been a bed of roses / People still look down their noses / I was born without the icing on the cake”), Smith’s world-weary, soul-drenched delivery manages to give the story real credibility and pathos. Nobody sang country soul so forsaken and low as Sammi Smith.

7. “Birmingham Blues,” The Birmingham Jug Band (1930). A raucous instrumental stomp-down from a great, forgotten Birmingham band. The Birmingham Jug Band recorded only eight songs at a single date in 1930, and though the band’s membership remains cloudy, the group’s prominent, blustering harmonica may be that of Jaybird Coleman, the Bessemer harp-blower who recorded a number of impressive solo sides in his own right. Ben Curry, a medicine-show entertainer also known as “Bogus Blind” Ben Covington (“Bogus” because he could in fact see), was likely another member of the group, alongside other players known to us only as “Dr. Ross,” “One-Armed Dave,” “Honeycup” (on jug) and “New Orleans Slide” (washboard). The hell-for-leather harmonica, steady low-blowing jug, and a wonderfully ragged mandolin give the tunes a drive unsurpassed by any of the era’s other jug bands. Almost half of the songs recorded by the Birmingham group consist of essentially the same melody—their “Birmingham Blues” closely echoes their “German Blues,” “Giving it Away,” “Getting Ready for Trial,” and others—but each time and with some variation the band proves it can play the hell out of that particular tune. Other instrumental odes to the city would be recorded in later years (Duke Ellington’s “Birmingham Breakdown” is a good one, besides the two discussed elsewhere in this Top Twenty), but Birmingham has never sounded better, freer, or wilder than in this blues. (Anyone out there, incidentally, who believes the worn stereotype that the music of the blues is a depressive and mournful thing had better listen to this record and get right.)

8. “Backin’ to Birmingham,” Lester Flatt (1972). The story: A novice trucker, unable to get his rig out of reverse, backs a semi full of steel from Chicago to Birmingham. A throwaway novelty number, but performed with authority and good humor by bluegrass legend Lester Flatt.

(Several other road songs, while we’re on the subject, make stops in Birmingham: Emmylou Harris’ “Boulder to Birmingham”; John Hiatt’s “Train to Birmingham”; Keith Whitley’s “Birmingham Turnaround.” Birmingham occupies a significant space in the center of Chuck Berry’s hit “Promised Land,” arguably the best of all American road songs. In that song “motor trouble” turns into “a struggle, halfway across Alabam,” the Greyhound bus breaking down and leaving the singer “stranded in downtown Birmingham.” Mirroring the tumultuous 1961 route of the Freedom Riders from Virginia to New Orleans, Berry’s song positions Birmingham at the heart of an unwelcoming South, a stopover point decidedly in contrast to the ultimate “Promised Land” of the title. The song ends with the singer boarding a plane and finally touching down (“Swing low, chariot, come down easy”) in Los Angeles.)

9. “Alabama,” John Coltrane (1963). John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” recorded in November 1963 for the Live at Birdland album, stands today as one of the most celebrated works of an established master. According to most commentators, it is at least in part a reflection on the deaths of four Birmingham girls, killed by explosion only two months earlier. Some listeners have claimed that Coltrane built the composition on the cadences of a speech by Martin Luther King, possibly his funeral oration for those girls. Coltrane himself was more oblique in defining his inspiration: “It represents, musically, something that I saw down there translated into music from inside me.” What comes out of Coltrane is profound, mournful, and—ultimately, above all—beautiful. LeRoi Jones, in the original liner notes: “I didn’t realize until now what a beautiful word Alabama is. That is one function of art, to reveal beauty, common or uncommon, uncommonly.” The song works in a kind of tragic idiom that parallels Shakespeare or Sophocles. Coltrane exposes us to the loss, the waste and hurt of human experience, but, as in the great tragedies, we can see reflected in the suffering suffering’s own antithesis: in the face of our capacity for destruction we remember again our capacity also for beauty, our profound potential to do better. Coltrane’s “Alabama,” like any art that lasts, transcends its historical moment, opening up the broader human experience, and leading us further toward understanding.

10. “Birmingham Jail,” Darby and Tarlton (1927). The most ubiquitous of all Birmingham song lyrics is the old, slow-waltzing ballad verse, “Write me a letter, send it by mail / Send it in care of the Birmingham jail.” The tune, commonly known as “Down in the Valley,” was a traditional folk song dating back before the turn of the 20th century, but in the 1920s the song, with the famous verse, became equally well-known as “Birmingham Jail.” The addition was apparently the work of Jimmie Tarlton, who claimed to have spent time in the jail on charges of moonshining. Tarlton recorded it in 1927 with his musical partner Tom Darby, and the song and its flipside—“Columbus Stockade Blues”—both became major sellers and staples of the southern country repertoire. The duo’s success with the tune moved them to record it again the following year, releasing it as “Birmingham Jail No. 2,” and in 1930 they gave the public more of what it wanted with an entirely new composition, titled “New Birmingham Jail.” The Magic City seemed to capture the imagination of these singers, who also recorded songs titled “Birmingham Town” (which boldly announces of San Francisco, “She’ll never be a town like Birmingham”) and the instrumental “Birmingham Rag.” “Birmingham Jail,” meanwhile, would be often recorded: by Alabama’s Stripling Brothers, by Eddy Arnold, by Peggy Lee, by Roy Acuff and Leadbelly and more. Little remembered today, Darby and Tarlton recorded over 60 sides between 1927 and 1933, helped pioneer the use of the slide guitar, and, with their heavy-harmonied, often-bluesy sound, proved influential to the development of country music. Interestingly, the Birmingham jail would become world-famous a few decades later, not for a letter sent to it but a letter sent from it, Martin Luther King’s historic “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

11. “15 Miles from Birmingham” and “Back to Birmingham,” the Delmore Brothers (1938, 1940). Another song about Birmingham letters (“Got a letter from Birmingham just today”) and Birmingham jails (“Oh, the jails in Birmingham sure are gay”), the Delmore Brothers’ “Back to Birmingham” is loaded with nostalgia; even in those jails, the song reminisces, “they give you conditioned air.” For all the wanderlust rambling of their repertoire (“Leavin’ On That Train,” “Ramblin’ Minded Blues,” “Honey, I’m Ramblin’ Away,” and a whole catalogue of songs about rivers and railroads), the Delmore Brothers sang often also of a sharp yearning for home. “Back to Birmingham,” though quick-tempoed and sometimes humorous, reflects a characteristic Delmore sadness, a longing for rootedness. “It’s the best place I have found,” the brothers sing of Birmingham, one of many hometowns in their real, nomadic career: “gonna quit my running round.” Born in Elkmont, Alabama, into a family of sharecroppers, the Delmores proved a profoundly original and influential country music act in the 1930s and ‘40s, known for soft harmonies, speedy guitar work, and a bottomless songbag of brother Alton’s sophisticated compositions. Both of their Birmingham songs contain all of the classic Delmore ingredients: the interplay of guitars and harmonies, the competing themes of wandering and home, the competing tones of amusement and deep-seated sadness. From “15 Miles”: “So sing a song, it won’t be long ‘til I come back again; I’ll ramble back again.”

12. “Tuxedo Junction,” Erskine Hawkins (1939). In the first decades of the 20th century, Ensley’s “Tuxedo Junction,” marked by the intersection of two streetcar lines, was a small but busy commercial hub, and a center of African American social life. In its heyday the Junction boasted a string of shops (one of them sold tuxes), black fraternal organizations, and night clubs, wherein dancers moved to live music from Birmingham’s best jazz players. People came from all over, the song said, “to get jive, that southern sound”: “to dance the night away.”

Trumpeter Erskine Hawkins was born in Birmingham and attended Industrial High School, where he studied under the legendary music instructor Fess Whatley. In college he became bandleader to the already-celebrated Bama State Collegians, whose members followed him to Harlem in 1934 to become the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra. In 1939 they cut “Tuxedo Junction,” an instrumental number which Hawkins named in honor of the hometown scene where he had once played. Originally relegated to B-side status (behind “Gin Mill Special”), “Junction” surpassed expectations to become Hawkins’ most popular song. New York lyricist Buddy Feyne, working from Hawkins’ description of the place, added words. Glenn Miller recorded it and it hit number one. An anthem of the World War II era, it jumped and swung from jukeboxes across the country, but nowhere more proudly or frequently than in Ensley. In 1940, a Birmingham Post article described the song’s constant playing on Junction nickelodians: “A shoemaker down the street drives his nails all day long to the swing of the music. Waiters in a café on the other corner do their jobs to its beat. Even the dishes seem to catch the rhythm of the piece. A barber up the street cuts hair to it.” The reporter continued: “All that music means nickels coming in, and Tuxedo Junction’s cash drawers can use some nickels now. It’s not the corner it used to be.” Sure enough, though the dance halls and businesses still stood in 1940, the tune was then already an homage to fading glory. Streetcar service ended, and the Junction was no longer a junction. All but one of the original Junction buildings (the historic Nixon building) were razed. When segregation came to Ensley, white residents pulled out in large numbers. The steel plant, long the heart of the Ensley economy, closed down. Poverty, crime, and homelessness went up. In the ‘80s the Nixon building was revived briefly as a music venue, this time for punk rockers, but that too passed.

Today the famous tune lingers as a reminder of a heyday past, and as a call to rise again. Around Ensley “Tuxedo Junction” is not yet forgotten: this summer the Erskine Hawkins Park, situated behind the Nixon Building, hosted its 24th Function at the Junction, an annual music festival (Hawkins himself was a regular participant at the event until his death in 1993). Plans for a Nixon Cultural Center, spotlighting the spot’s cultural legacy, are also underway.

13. “Birmingham,” Drive-By Truckers (2002). The Drive-By Truckers’ “Birmingham” is a sweat-stained and beery anthem to the roots and future and passion and swelter of the city. “Most of my family came from Birmingham,” it says; “I can feel their presence on the street / Vulcan Park’s seen its share of troubled times, but the city won’t admit defeat.” Frontman Patterson Hood variously drawls and slurs and yells and moans the lyrics which near the end of the song turn into a scraggy incantation guaranteed at any live show to really stir up the hometown crowd. The song is a part of the Truckers’ 2001 double-album, Southern Rock Opera, a loving and unflinching statement of the “southern thing” at the turn of the 21st century. The album offers a loose, semi-fictional storyline that plunges deep into southern mythology and identity, pulling into its scope Muscle Shoals soul, the Civil Rights struggle, the Lynyrd Skynyrd plane-crash, booze and family and the Devil—and, out of it all, loud and intemperate, gut-busting Rock. Birmingham figures prominently into the whole thing, nowhere more so than in this blistering hymn. Patterson Hood, deep into his spell-casting, is just about screaming by now—“Magic’s City’s magic’s getting stronger”—and the song concludes: “No man should ever feel he don’t belong, in Birmingham.” The song ends and the hometown crowd is in a frenzy; somehow its members too have become as sweat-soaked as the band.

14. “Birmingham, Alabama,” R.B. Greaves (1969). R.B. Greaves, nephew of soul-stirrer Sam Cooke, had one of the least likely bios in soul music history. Born Ronald Bertram Aloysius Greaves III on an Air Force Base in Guyana, South America, he was raised in the United States, on a Seminole Indian Reservation. In the ‘60s he relocated to England, where he fronted a group called Sonny Childe and the T&Ts, before returning to America to pursue an R&B career and a brief flirtation with country music—but ultimately joining the ranks of the one-hit-wonder for his only real success, 1969’s “Take a Letter, Maria.” Recorded at Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals, “Maria” was itself something of an oddity for a hit record, framed as the first-person narration of a businessman who, the previous evening, caught his wife cheating and now dictates to his secretary his plans to get a divorce and split town. In the process of dictation, he realizes his love for the secretary and incorporates her into his escape plans, beginning with a romantic dinner after work. (Maria is ambiguously Hispanic, and the song’s mariachi horns suggest that perhaps the two, in their “new life,” will head somewhere south of the border.) On the whole, Greaves’ work languished between the poles of Lou-Rawlsian smooth pop and the earthier soul for which Muscle Shoals was better known, and beyond “Maria” Greaves met with little success, his recorded output limited and spotty.

Of interest here, though, is another song from the self-titled 1969 album that gave the world “Maria.” Written by Murray MacLeod and Stuart Margolin and covered also by Harry Belafonte, “Birmingham, Alabama” isn’t exactly hit material, but it’s catchy enough—and the way Greaves consistently belts out the city and state name will at least make any local listener feel good. The song’s best line: “Jesus says, ‘You’ll be shuffling coal till your dying day – in Birmingha-a-am, Alabama.’”

15. “A Small Town They Call Bessemer,” Jazz Gillum and Memphis Slim (1961). A separate, if shorter, list might be compiled of the best Bessemer songs—among them, Ma Rainey’s “Bessemer Bound Blues,” Tampa Red’s “Bessemer Blues,” and Big Joe Williams’s “Bessemer Baby.” The best of the Bessemer songs, arguably, is “A Small Town They Call Bessemer,” in which the singer threatens to get “mean and evil” and move from Bessemer “back to Birmingham” if his woman doesn’t treat him right. Gillum had recorded the song back in the ‘30s as “Birmingham Blues,” but the 1961 version benefits from Memphis Slim’s funky electric organ vamping and rolling and jumping beneath Gillum’s drawl.

16. “The Magic City,” Sun Ra and his Solar Arkestra (1965). Sun Ra biographer John Szwed contends that “1965 was a turning point” for Sun Ra’s music; and that year’s album The Magic City, Szwed notes, “was the clearest signal of the change.” If Sun Ra had already played at the outer limits of jazz, here he stretched his soloists and listeners further into unmapped experience. The album’s title track swallowed the entire first side of the record, sketching for a near half-hour a sonic landscape that is part Birmingham, part outer-space: it was a kind of homecoming, but on Sun Ra’s terms, a revisioning of the city in which the man and his music were first born. Sun Ra plays (sometimes simultaneously) piano and Clavioline, an early synthesizer evoking the ominous explorations of late-night black-and-white space flicks. The instruments play against and with each other, interacting also with the comings and goings of bass, drums, clarinet, piccolo, and flute. Fifteen minutes in, the performance explodes, instruments erupting at once. There are five saxophones, sometimes screaming. Throughout the piece, as in much of Sun Ra’s work, an alternate universe emerges from the shifting layers of sound. In the Arkestra’s hands, the Magic City bends, opens, and expands—a city of magic, of Magi, of imagination—to become portal into a deeper cosmos. (For more on Sun Ra, see the feature article in this issue.)

17. “Birmingham Bull” (“Didn’t He Ramble”), Ernie Marrs (1963). Matching new words to old tunes was a common practice among participants of the Civil Rights Movement (as with the revised “Great Day for Me,” # 5 above). Nineteenth-century spirituals were revived, their lyrics often adjusted to link the contemporary freedom struggle to the struggle begun in slavery (“Oh, Freedom,” “Gospel Plow,” “Wade in the Water”); union songs lent their activist stances to the Civil Rights cause (“Which Side Are You On?”); commercial pop songs were retooled to reflect the times (“Hit the Road, Jack” as “Get Your Rights, Jack,” “The Banana Boat Song (Day-O)” as “Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long,” even “Land of 1,000 Dances” reclaimed as a freedom chant). A number of topical folksingers emerged from the Northeastern college and coffeehouse scenes to give their hands and voices to the movement, adding still more songs to the cause’s songbook. Ernie Marrs (best known for his version of “Plastic Jesus”) recreated the old standby “Birmingham Jail” as “Bull Connor’s Jail” in the crucial year of 1963. The same year he borrowed from the traditional English ballad “The Darby Ram” and the New Orleans Dixieland staple “Didn’t He Ramble” to cut down to size one of the most notorious villains of the movement. Pete Seeger picked up Marrs’ song in Birmingham and performed it in June of ‘63 at his famous Carnegie Hall concert. The protest-rooted Broadside Magazine ran the song the same month. A few of Marrs’ verses:

As I went down to Birmingham upon a summer day

I saw the biggest Bull, sir, dry up and blow away.

And didn’t he ramble, didn’t he ramble

Didn’t he ramble till his size was whittled down.

His belly it was huge, sir, you should have seen it flop

It dangled to the ground, sir, till I thought his skin would pop…

His rear was round and fat, sir, how large I cannot tell

His head was even fatter, you should have seen it swell…

The song ends with this advice:

But if you see a Bull, sir, that tries to throw a scare

Just give his tail a pull, sir, and let out all his air

18. “Birmingham Black Bottom,” Charlie Johnson’s Original Paradise Ten, featuring Monette Moore (1927). “Stompin’… rompin’ … do that Birmingham stomp!”: it is a tune which, literally, demands dancing. The “Black Bottom” was a popular dance style that, during the Jazz Age heyday spread from urban black America into the flapper culture and—briefly, at least—into the mainstream national consciousness. The term “Black Bottom” played on several levels at once, allowing for it a popular and flexible usage within the jazz vocabulary. Many black neighborhoods in urban spaces across the country picked up the label “Black Bottom,” and from one or more of these “bottoms” emerged a dance of the same name. In an era of overnight dance crazes, this one caught on, popularized in such recordings as “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” and Jelly Roll Morton’s “Black Bottom Stomp.” (The term’s further, punning meaning is evident in Rainey’s declaration, “Wait until you see me do my big black bottom, it’ll put you in a trance.”) In the late 1920s vocalist Monette Moore sang with pianist and bandleader Charlie Johnson’s Paradise Ten, the house band at Small’s Paradise, one of Harlem’s top jazz clubs. Their “Birmingham Black Bottom,” while lacking much more than a titular connection to the city, has everything a listener, or a dancer, could want from the black bottom tradition—a lively beat, boisterous and wailing instrumentation, gleeful vocals, and sweet invitation to sheer abandon.

19. “Sweet Home Alabama,” Lynyrd Skynyrd (1974). What do we say of “Sweet Home”? While some would doubtless argue that it does not belong on this list at all, others would rank it as the ultimate Birmingham song—even if its reference to the city is brief (and, well, complicated). Whether you love “Sweet Home Alabama” or hate it, or feel for it a simultaneous attraction and revulsion that is neither love nor hate or is, maybe, both—surely, in the end, you must confront it as one of our city’s unavoidable songs, perhaps even its defining song.

“Sweet Home Alabama” is, after all, on most of our license plates now (replacing another tune, “Stars Fell on Alabama,” a song most Alabamians have by now forgotten). This song, moreover, is in our blood. American tourists—people who have never set foot in this state—will hear it suddenly in far-off countries and will identify, will feel a kind of patriotic rush, and will sing along. Because the song isn’t even about Alabama anymore, if it ever was; it’s about home. And it is catchy, and it is loud. A few years ago, a Birmingham tourism group came close to adopting “Sweet Home Alabama” as its own motto, adjusting the lyrics to inspire both pride and commerce: “in Birmingham,” a proposed slogan ran, “they love the shopping.” I wish I was kidding.

That is, after all, the crucial line—the controversial line, the one that incorporates (for we are the they) all of us. Forget the mythic Neil Young squabble (a legend artfully debunked on the Drive-By Truckers’ Southern Rock Opera, mentioned above). What are we to do with a line like “In Birmingham, they love the governor,” recorded during the long reign of George Wallace? Some Skynyrd apologists have claimed that the doo-woppy chant, “Boo, boo, boo!” which follows that line signals the band’s actual rejection of Wallace and all that he stood for. But surely that is far-fetched, revisionist and wishful thinking. So what do we do with the line? Does liking the song mean loving the governor? Does loving the governor have to mean supporting his segregationist poses? Or is this merely a celebration of populism—or a defiant pride in who we are, despite all our obvious warts? What, exactly, does it mean when Alabama football fans adopt a song (Roll, Tide, Roll!) that claims support for the man who famously stood in their own schoolhouse door to block black arrivals? Does the song speak to Wallace’s alleged repentance and transformation, already underway by 1974? Ambiguities pile higher with the song’s next mysterious line, “We all did what we could do.” If only we knew what this meant, the song’s mysteries would stand revealed. And, really, how can Watergate not bother these guys? Is that swaggering indifference okay, even in a pop song?

What I guess I am saying is: should my conscience bother me if this song is, defiantly, in my bones? What does that song, and that line, mean for Birminghamians now?

I have written more about this song than I meant to. The upshot: “Home” is a complicated thing.

20. “Birmingham,” Randy Newman (1974). On 1972’s Sail Away, Randy Newman’s satirical and sometimes scathing voice inhabited such songs as the title cut, in which a slave trader, like a tacky salesman, hawks America to potential slaves; “Political Science,” which espouses a blanket American foreign policy of dropping “the big one” to “see what happens”; and “God’s Song (That’s Why I Love Mankind),” in which a cynical, contemptuous Creator torments his people with plagues and gross destruction simply because He can, and because His ridiculous victims will, absurdly, love Him anyway. Later, Newman’s only real hit, the Jonathan-Swiftian “Short People,” would inspire protests among groups of, well, short people who took the song’s satire seriously. But Newman’s sarcasm, bite, and voice-throwing shenanigans were at their sharpest on the concept album Good Old Boys, 1974’s follow-up to the critically-acclaimed Sail Away. At first glance Newman may seem a snarky outsider further maligning a cracker culture which, for all of its faults, may not deserve cheap shots from a far-off California hipster. But Good Old Boys is a complicated, challenging, and empathetic work which has become a southern classic. The opening track, “Rednecks,” takes the perspective of one of the good old boys of the album’s title, and does something that only Randy Newman would attempt on a could-be pop album: it crafts a catchy chorus—one that gets stuck in your head, one with which you are immediately compelled to sing along—around the phrase “we’re keeping the niggers down.” And then, just when we are ready to put the album’s rednecks in an easy and predictable box, our sense of moral superiority all afire, we encounter the record’s second track: “Birmingham.”

Again the perspective is first person, the song’s speaker a steel mill worker (the same redneck-speaker of the previous song?) with a wife named Mary but called Marie and a dog named Dan. Again, the chorus is catchy and singable, proudly proclaiming Birmingham the “greatest city in Alabam.” If Newman’s work drips often with irony and satire, and if the song immediately previous had lambasted the South and its unthinking rednecks, “Birmingham” feels disarmingly, perplexingly genuine: the way Newman sings “the greatest city in Alabam,” he may as well be proclaiming it the greatest city on the planet. (The song is convincing enough that Del McCoury could later cover it as a bluegrass song—straight-faced, no trace of irony or condescension anywhere—and again it works.) Two tracks into Good Old Boys, then, we are forced to reconsider what Randy Newman is up to. By the time the record’s first side is over, we have been able to somehow, simultaneously laugh at, loathe, pity, feel for, laugh with, and even identify(!) with Newman’s rednecks: they have played into and quickly escaped our stereotype, confronted us and confounded us as real, complex personalities. Despite everything else, even the worst, for three minutes and twenty seconds we can believe whole-heartedly that “There’s no place like Birmingham,” and that for this place we are lucky.

This one could be our city’s theme song.

Greencup is Dead: A Eulogy

Note: The following article, eulogizing Birmingham, Alabama’s Greencup Books, first appeared in the November 2009 edition of Pavo, the “online magazine” of arts and culture in the “Magic City.” Like Greencup, Pavo is now also defunct and, I think, its absence is a loss to the community.

Each month, Pavo organized itself very loosely around a different theme, and in keeping with the Thanksgiving season, the theme for November ‘09 was “gratitude.” Elsewhere on the website that month, Pavo contributors were asked to name a few things for which they were grateful. For what it is worth, here is my list, followed by the eulogy:

The last page of The Great Gatsby; the first two pages of Tropic of Cancer; page thirteen of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men; the guitar solos in “Folsom Prison Blues” and “Pale Blue Eyes”; Frankie “Half-Pint” Jaxon; Lily Tomlin’s face in that one scene in Nashville; carrot juice; Buster Keaton; my parents, and brother, and sister-in-law, and nephews; fried oysters; early bedtimes.

* *

Greencup Books is dead.

Long live Greencup Books.

This is not easy to write—hopefully you know it already, and I am not the one breaking the news—but Greencup is officially no more. Struggling since it opened to keep its head over water, the not-for-profit bookspace on Richard Arrington Boulevard has finally closed its doors for good.

Of course, the day was bound to come. As owner Mike Tesney has been saying a lot lately, “It was never a question of if; it was a question of when.” For months, Greencup’s website had been soliciting donations in an effort to keep things going, relying on the community’s faith in and support of the vision. Certainly, there were lots of factors behind the final decision. Turnout for Greencup events had always been unpredictable at best; a new construction project across the street recently consumed a good stretch of the store’s parking, making things worse. Greencup’s own building, meanwhile, needed a few thousand dollars to get itself quickly up to code. Many locals considered the very premise of Greencup hopelessly quixotic from the get-go. When, in October, word came that the store only had a few weeks left, the announcement, however unwanted, surprised nobody.

Greencup ended, with a fitting touch of symbolism, on the Day of the Dead, Sunday night, November 2. Next door the Bare Hands Gallery hosted its annual Dia de los Muertos parade and festivities; all night, skeleton-faced revelers passed by Greencup’s open doors, some of them stopping in for a read, for conversation, to make a purchase or use the bathroom. Some walk-ins browsed the store that night for their first and last time. Friends came in and paid their final respects. And a kind of death hung over everything.

* *

I am a twelfth-grade English teacher, and for the first few minutes of class every Friday, my students write about whatever they want. Topics range widely. Several Fridays ago, one of my students wrote this:

“I went to Greencup Books for the first time yesterday. I’m usually a Barnes and Noble kind of guy,” the student admitted, “but I was hanging out with my friends and we needed someplace to go. It was really exactly like I expected, except that it smelled like smoke instead of used books. I used to read books from the same series at the library and the person who read them last always wore really strong perfume. But I digress.

“The thing I noticed about the bookstore: at surface level, it’s really not as good as a megachain. I could only find one of the books I looked for (Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man), and the place was hardly organized at all. So I’ve been trying to figure the appeal of these used books stores, and all I can chalk it up to at this point is that reading must not be as much of an individual event as I thought it was. I think books need to be passed hand to hand. That’s why I like to find used books instead of buying them new, and that’s why people who love to read love libraries.”

While it lasted, Greencup hosted rock shows, art shows, writing workshops and readings, and it offered local writers design and publishing services for their own work—but the followings that resulted never established enough of a steady momentum to keep things running in the face of great odds. Russell Helms opened the store in February of 2008; Helms moved to Kentucky and Tesney took ownership in July of the same year. From its inception, Greencup was an anti-capitalist venture—a concept, Tesney says, which most people had trouble swallowing. (“I got tired of explaining it,” he says, adding that the idea of an anti-capitalist bookstore caused some visitors to laugh outright.) But Greencup’s thing all along was about fostering creativity and community, about facilitating good reads and conversation, and doing so within a framework that defiantly rejected the machinery of money-making. Books were cheap. Workers volunteered their time and were paid in food and maybe gas money. More than a store—the word “store,” in fact, is almost entirely misleading—Greencup existed above all to offer a community space rooted in art and music and books. It boasted comfortable old couches and a wide selection of politically radical zines. Performers came from all over the U.S., even from outside the country, to perform in the upstairs space; the standing cover was “about five bucks” for any show. Last year, Greencup hosted an alternative media fair for zinesters, do-it-yourself bookmakers, and indy record labels across the Southeast. When Cave 9, the all-ages punk venue, closed its own doors earlier this year, its operations moved briefly into Greencup. The founding ideal, Tesney says, was to be “an open space for everybody.” The design was aggressively anti-establishment, and there was in the whole thing a particular spirit of youth.

“I’m disappointed that more people didn’t take advantage of this place,” says Devon Thagard, the store’s most loyal volunteer/worker, currently a student at the University of Alabama. “Overall I am grateful for the experience and all the things I got to learn while working there. I only wish that more people could have had the same experience.”

One of the last scheduled events at Greencup was a return performance by Insurgent Theatre, a radical theatre troupe from Milwaukee. A description of their show, “Ulyssess’ Crewmen,” ran on Greencup’s website: “We join the struggle against the imperial economy arranged by bureaucratic trade regimes that make us all complicit in the exploitation and destruction of others. We question and investigate the psychosexual underpinnings of both this bureaucracy and those of us attempting to rebel against it. We use Homer’s Odyssey as a framework to stage these struggles in a single claustrophobic scene between two people, one of whom is bound and gagged.”

Also on the ticket that night: Mangos with Chili, “The Bay Area’s only cabaret show for transgenders of color.”

In Birmingham, a line-up like that could only happen at Greencup.

Nobody came.

* *

The box-store chains and internet booksellers have, for some time now, made it easy to quickly obtain any book you may want; but a few months back a friend commented that he still preferred to let the tricks of serendipity dictate his reading life—to let, in other words, his reads find him. I tend to agree with that philosophy. The best of the books that I have accidentally discovered hold a certain kind of power in my memory; there is the sense that book and reader stumbled upon each other unsuspectingly, through some turn of fate, forging something unique in the encounter. At McKay’s in Chattanooga I discovered Appreciation by Leo Stein, Gertrude’s brother, and the book became, for me, an unexpected personal classic; at the Alabama Booksmith I came across Chris Bachelder’s U.S.! and Charles Portis’ The Dog of the South, two of the funniest books I have ever read; I left a store in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, with Kenneth Fearing’s The Big Clock, a 1940s noir title I never would have sought out, but a read which now hangs heavily over my memory of a favorite road trip; and once I found, deep in the recesses of a Chapel Hill bookstore, a well-worn copy of Woody Guthrie’s Born to Win, a book I had sought since I was sixteen and, having finally forgotten it, found by mistake a decade later. Bought and read by accident, these books carry a particular kind of weight and mystery in my reading experience. Though serendipity can do its work in a Barnes & Noble too, the really meaningful accidents seem to occur in smaller, less predictable environments.

This was one Greencup’s greatest assets: it was the best place in town for the unexpected find.

* *

Some titles I’ve acquired from Greencup over the last couple of years:

• The Life of Black Hawk

• A book of conversations with Eudora Welty

• Jerry Kozinski’s Being There

• The second issue of “8 Letters,” a zine on knuckle tattoos

• A copy of Beowulf

• The first issue of Cumulus

• “Klaudt Family Specials,” a bio-songbook from the gospel-singing “Klaudt Indian Family” of Doraville, Georgia

• “Well Glory!” – another paper-bound songbook from the Willcutt family, the “sunrise devotional group” at Birmingham’s WBRC radio

• John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction

• Jim Thompson’s Pop. 1280

• Scratchy 45s of Joan Jett’s “I Love Rock and Roll,” Desmond Dekker’s “Israelites,” and (in its original sleeve, no less) the Mick Jagger/Jackson 5 “State of Shock”

• The Alabama Wurlitzer at its Best, a long-playing record from 1986 featuring “Big Bertha,” the Alabama Theater’s signature organ

• From 1980, a Japanese handbook of “handy” English phrases (“I’m getting out of this crummy business”; “My wife goes through my pockets”; “He becomes a victim of Demon Rum”; “I hear you’re some pianist”; “It’s a job with sexual flavor”; “Some typewriter I got”; “Somebody framed you!”)

Some of these I bought with money. Most I got as trades.

As I write this, I am listening to the Alabama Wurlitzer.

* *

The Saturday after its official closing, Greencup hosted a final, cash-only, friends-only sale, everything 50% off to Greencup supporters. “This is a thank-you sale,” Tesney announced, “not a let’s make more money thing.” Visitors were encouraged to bring flashlights in case the power had already been cut off.

I was not there, and I do not know if there was electricity or not. But it does make for an effective image of how Greencup finally ended: quietly, stubbornly, its most faithful followers rummaging with flashlights through stacks of old books.

* *

Pavo’s theme this month is “gratitude”: a good fit, I think, for this eulogy.

Much could be said about the ups and downs of Greencup Books—the trials, the successes, the frustrations—but let’s leave it for now at a simple “thanks.” For offering, for a little while, an important community space; for encouraging good reads and the exchange of ideas; for providing a wide-open venue for music and experiment; for reminding us that, perhaps, reading is not as much of an individual event as we might think.

Mike Tesney is moving to Tuscaloosa, where he plans to try it again with a similar bookspace; besides the books, the Tuscaloosa outfit will be equipped with a recording studio, and Tesney is already working with connections at the University of Alabama to build a collaborative base. Up in Kentucky, Greencup founder Russell Helms works towards an MFA and writes. Birmingham, meanwhile, is left with a hole that wants filling.

And so, I say, a toast:

Here’s to further Birmingham endeavors as impossible, as maddening, and as necessary as our late store.

Long live Greencup Books.

Amen.

Kirk Withrow, Cigar Box Guitarist

Cigar box guitar by Kirk WIthrow

Kirk Withrow is a head and neck surgeon at UAB. He is a husband and father and an avid rock climber. He is also, passionately, a cigar-box guitarist and prolific “garage luthier,” a creator and player of unlikely hand-crafted instruments. He has just finished his latest collection of songs, home-recorded on homemade guitars: a kids’ album of animal songs, called Cows and Crocs and Dirty Socks.

Withrow has a lot going on. It’s not easy, he admits, balancing his creative life with family and career. “You have to cut things out—like sleeping and eating, and exercise.”

Weighty sacrifices, perhaps, but cigar box guitar enthusiasts are fueled by an uncommon drive and intensity of purpose. The instrument comes to embody, for them, a whole philosophy of art, self-expression, and living. It becomes an obsession. It gets inside you, and changes you.

“The type of people,” Withrow says, “that would make and pursue the cigar box guitar, they’re always a little bit different.”

Every cigar box guitarist seems to have his conversion story: on this day, the story goes, and in that moment, everything changed, and everything ever since has been different.

Withrow’s moment occurred four years ago. A patient—Phil Draper, a cabinet-maker from Decatur—gave him his first cigar box guitar. Draper had spent a few days in the hospital and Withrow had gotten to know him during his stay; Draper had told him about the guitars and Withrow was intrigued. He began researching the instruments online, where he discovered an entire community. When Draper gave him a guitar of his own, he fell in love.

Ironically, Withrow remembers, he had been determined to get out of his shift at the hospital the night Phil Draper came in—he was supposed to help a friend move that afternoon, and afterwards, he hoped to relax with a couple of beers. No one, though, would switch shifts with him; he reported to work, and his fate was sealed.

“It’s interesting to think what would have happened if he had not come in,” Withrow says, “or if I had gotten out of my shift.” As it happened, though, the chance encounter left a huge impact on Withrow’s life, an impact which has been much more than merely musical.

“It’s made a huge difference. It changed the way that I act, the way that I think, and a lot of the people I’ve met. Without it,” he speculates, “I guess I’d have to watch football or something—and I don’t want that to happen.”

That first guitar set off a chain reaction that is still going. Once he’d played a cigar box guitar, Withrow discovered he had to make one; then another one and another, each time searching for a new design and a new sound. With a couple of climbing friends he started a band, Buckeye, and recorded an album, Box Fetish: a collection of “very-much amateur recordings,” he says, a lot of old blues and banjo tunes and some originals, played dirty, raw, and loud. His next two CDs, Hogtie the Devil and Yesterday Will Be Better, both self-produced solo efforts, featured for the most part a repertoire of traditional old-time songs. Another project, Monks of the New Order, was an experiment in avant-garde noise. Then there’s the kids’ stuff: two years ago, after the birth of his son Silas, Withrow recorded Lullaby, a collection of instrumental tunes performed on original instruments and crib toys. “I imagined it,” he says, describing his concept for the album, “as the last day in the womb and the first day out of it,” a sonic chronicle of a child’s emergence into the world. Cows and Crocs and Dirty Socks is Withrow’s latest effort.

It’s hard for Withrow—or for anyone who visits his workshop and music room—to believe that it has been only four years since his cigar box conversion. He estimates that in those four years he has given away or sold about fifty handmade instruments. He has several on display and for sale locally at Naked Art, and he also sells them online, through websites like eBay and Etsy. The online sales, he says, go primarily overseas: he’s had customers in Spain, Italy, Israel, and elsewhere.

To make a simple, fretless, unamplified guitar, no inlay or frills, takes Withrow only about an hour. A more involved design will take ten or twenty. Fully functional instruments, the guitars double as works of art: carefully constructed out of found objects, each has its own aesthetic and personality. There is, also, the obvious novelty factor. “People will stop and look at it,” Withrow says. “People are surprised you can get that much sound out of it.”

That is, after all, the goal: to extract sound from the smallest, most ordinary, and least likely of sources; to create something useful and new out of something useless and old; to find and experiment with the music that is embedded in just about anything.

Before his moment of conversion, Withrow had struggled to find a musical voice or vehicle for his pent-up creative energies. On the guitar (the store-bought, non-cigar-box kind), he sounded, he says, like every other guitar player. He took up the banjo, but felt that he had quickly reached his own limits in exploring what that instrument had to offer him: “Banjo,” he explains, “is a versatile instrument, but I could never get it to sound like anything but a banjo.” He wanted to take it someplace else, to “stretch beyond the normal range” of that instrument’s voice, but he found himself stuck and uninspired.

Withrow describes his music, in those, pre-cigar-box days, as stale. “It had gotten mundane, and I hadn’t been doing much—certainly not anything creative.”

The cigar box changed everything, opening up a well of creativity—not only as a musician, but as a woodworker and artist—which he had never before experienced. Once Withrow made his first guitar, he found himself hungry to make a second, then a third; each creation, he discovered, was distinct. “The next one will have a different sound,” he says, working on one. “I’ll make a guitar, then I’ll make one electric. Maybe I’ll make a volume and a tone control. Then I start working with battery-operated, self-contained amplifiers.” In the process of making guitar after guitar, he discovers ever-increasing possibilities to pursue the next time: an idea for an inlay design, for a handwound pick-up or for a resonator. The guitars multiply, fast.

“I’d never done any kind of woodworking,” Withrow confesses, but with the first efforts to make a guitar came a simple, empowering epiphany: “You just realize that you can do it.” Withrow’s guitar-making quickly led to other projects: paintings made from spray paint, scrap wood and Sharpies; charcoal-and-marker sketches; pendants and jewelry; wood-carvings and wall-hangings. After making so many guitars, he found that he had quality wood he didn’t want to throw away, and from those leftover materials he began making boxes, which he has also started selling.

* * *

The practice of making stringed instruments from cigar boxes—often with screen-wire strings strung down a broom-handle neck—is about a century and a half old. In recent years, a scattered community of musicians has developed from the cigar box tradition a culture of its own: what some practitioners go so far as to call a “revolution.”

“The biggest force behind that,” says Withrow, “is Shane Speal” of York, Pennsylvania. The self-proclaimed “King of the Cigar Box Guitar,” Speal started, in 2003, a Yahoo forum for “CBG” enthusiasts, attracting a membership of over 3,000. Speal is the producer of Uncle Enos, an irregularly published homemade magazine which bills itself as “the lo-fi voice of the Prim Rock Underground.” In its pages, he and other writers articulate a kind of running manifesto for their homemade music—and, more broadly, for the DIY (do-it-yourself) approach. “If you’re a musician,” Speal writes in one issue, “I encourage you to build a cigar box guitar or one of the other instruments highlighted in this issue. If you are in other arts, try something just as primal. Take toy camera photographs. Create comic strips using only rubber stamps…. Sing thru tin cans and wire. Drum on plastic buckets. Research and write the history of some forgotten hero in your hometown. Write, create, and produce your own zine.

“Because let’s face it, the world needs more deep art and new heroes.”

For the modern-day cigar box guitarist, the search for what Speal calls the “primal” is an attempt to strip music and art to their barest bones and most basic: to create something from scratch, and to do it yourself. “We want to play something true again,” Speal writes in another issue. “Something deep.”

There is often in the voice of cigar box players and makers a kind of missionary zeal, a cigar box mysticism and cigar box evangelism manifested in the telling of conversion stories and in the sharing of the cigar box gospel. The instruments are not simply means to creating music; for the true believers, the instruments are an entry point into a lifestyle and perspective that transcends the music to become something larger.

Community is a critical part of this culture. Spurred largely by the efforts of Speal, a network of like souls has developed, linking musicians and sparking friendships across the US and around the world. With several enthusiasts across the state, Alabama has become one focal point in that community. In 2005, Huntsville tattoo artist Matt Crunk launched the Alabama Cigar Box Extravaganza, an annual event featuring workshops, a guitar-building contest, and a line-up of performers from around the country. In 2008, the University of Alabama’s Max Shores spotlighted the festival and its community in a documentary film titled Songs Inside the Box. The film features performances by and interviews with a number of musicians, including Speal and Withrow. “They’re an odd bunch of characters,” Withrow says in the film, describing his fellow musicians, “but they’re about the nicest people that you’ll run across.”

* * *

Some instruments are born with something to say built-in already inside them: they come to life with a voice and a message beyond the control of their maker or player. In these instruments, indeed, the roles are reversed and the instrument plays its player; the musician becomes the means through which the wood and strings make their own inevitable statement heard. There are old stories and eerie ballads of fiddles and harps and guitars that possess their players, instruments that sing their own insistent songs as soon as they are touched—a fiddle, for example, that will only play “The Wind and the Rain,” or a flute that blows the story of a poor girl’s murder.

Kirk Withrow speaks of the songs that exist inside specific instruments, songs which belong to a particular guitar, that seem to emerge full-voiced from the new creation. “You make instruments for songs,” he says—“or, certain songs come with an instrument. The way you tune it up, a song pops out of it that you haven’t been able to play before.” In Withrow’s experience, a new instrument will liberate a particular song which no other instrument can get quite right. The discoveries of new songs within new constructions keeps him always working on the next instrument and toward the next sound. In this music, a dynamic, collaborative relationship links the maker/musician, the instrument, and the song.